You can learn more about local linearization and Newton's method on KA.\nonumber M_X(s)&=E\left[e^s \in (-2,2). There are some certain circumstances where Newton's method will actually fail to find a root. I'll get closer and closer to the root as a perform more and more steps.

I then repeat the process at the point on the curve which is the 𝑥-intercept of the first linearization. Essentially, I take the local linearization at a point in the interval, then I find the 𝑥-intercept of that tangent line. This is pretty tedious, so I would rather use Newton's method to approximate the roots within this interval. If you were to strictly only use IVT, the best you can do here is bringing 𝑎 closer and closer to 𝑏 and testing the values of 𝑓 that result until you find a value in the interval that is sufficiently close to 𝑐 (or you could start from 𝑏 and use smaller and smaller values).

Then by the Intermediate value theorem, there exists a 𝑐 ∈ (𝑎, 𝑏) such that 𝑓(𝑐) = 0, that is, 𝑐 is a root of 𝑓. Well first I would find an interval where 𝑓 is monotonically increasing or decreasing, such that 𝑓(𝑎) < 0 < 𝑓(𝑏). If the any option makes assumptions about what happens outside that box, don't select it, because there's no way for you to know those things from the information you've been given. In answering a multiple-choice question about values given by the Intermediate Value Theorem, imagine this box on your graph. But the important thing is, it definitely has to go between one and five, otherwise it wouldn't connect our end points! On the y-axis, our function could go lower than 1 or higher than 5 - we don't know. In that case we know the function can't go any further left than 0, or any further right than 10. Let's say our interval is and the end points are (0, 1) and (10, 5).

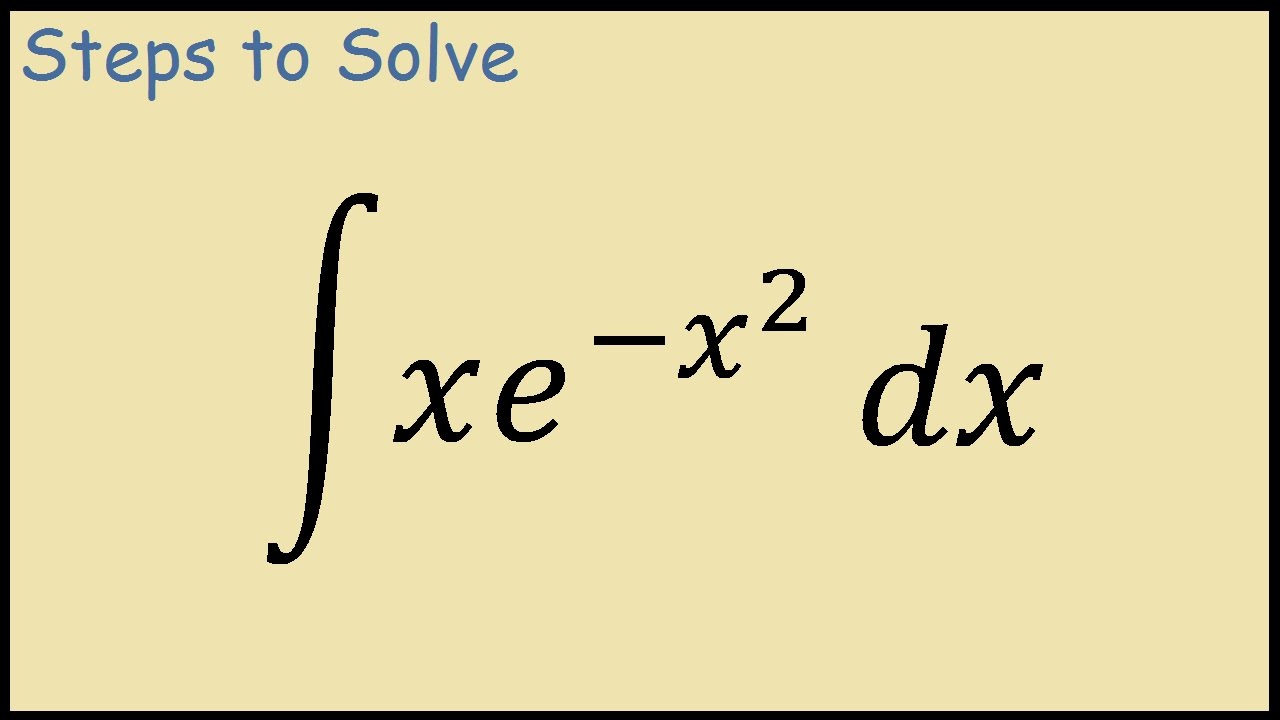

My problem is, that the result depends on what values I choose for my borders x1 and x2 (see below). We don't necessarily know what the function looks like, but we know where it can and can't go. I use the function randn() to generate all xi for the function f(xi) exp(-xi2/2) I want to integrate to calculate afterwards the mean value of f(x1.xn).

By "predictable" I mean that the limits for a point from the right and left side are the same as the point's value in the function.Ī simple way to imagine this is to pretend the continuous function occupies a box. The theorem basically says "If I pick an X value that is included on a continuous function, I will get a Y value, within a certain range, to go with it." We know this will work because a continuous function has a predictable Y value for every X value.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)